There’s a certain magic to shooting with a film camera that’s hard to describe. It’s the heavy, mechanical click of the shutter, the careful process of advancing the film, and the weeks of anticipation before you finally see your developed photos. For a long time, that deliberate, tangible process was what photography meant to me. Now, I pull a sleek piece of glass from my pocket, tap the screen, and an algorithm instantly captures a burst of images, merges them, and presents a perfectly lit, impossibly sharp photo. The journey from that mechanical click to that silent, computational flash has been fascinating, and it’s changed my photography in ways I never expected.

My work has involved digging into artificial intelligence for several years now. As Zain Mhd, I’ve spent my time trying to connect the dots between complex algorithms and the real-world experiences they shape, from gaming to creative tools. This dive into computational photography wasn’t for a technical paper; it started from my own curiosity. I wanted to understand what was happening inside my phone’s camera. I felt a disconnect between the photography I learned—built on aperture, shutter speed, and ISO—and this new world where software seemed to be doing all the thinking. This is what I found when I started comparing my old film shots to the AI-powered images I capture today.

Let’s break down this shift. It’s a story about letting go of old habits, embracing new technology, and finding a new balance between human skill and artificial intelligence.

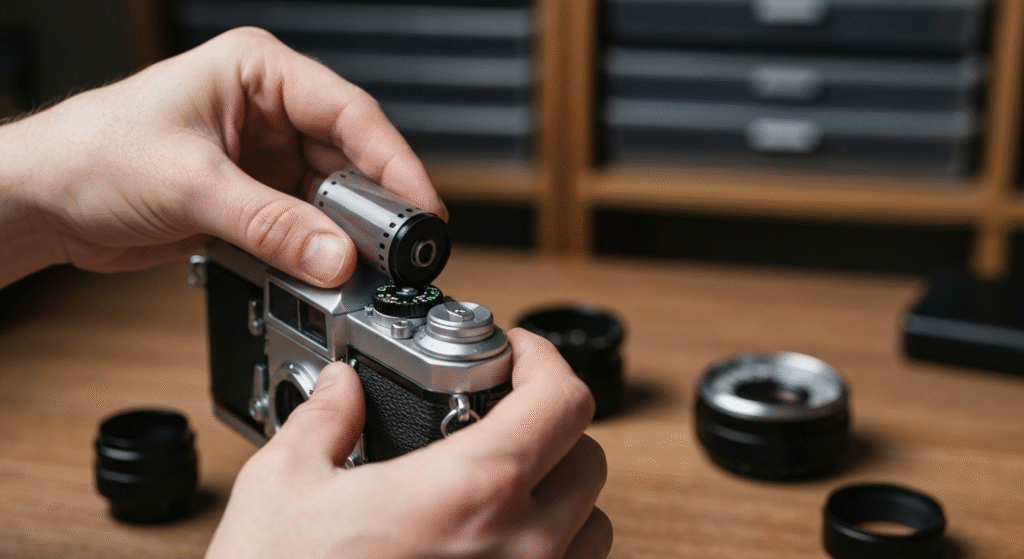

The Deliberate Art of Film Photography

Before we get into the AI, it’s important to remember where many of us started. Film photography is a craft of limitations. You have a limited number of exposures on a roll, and every single shot costs money and time. This scarcity forces you to be incredibly intentional. I would spend minutes composing a single shot, checking my light meter, and manually adjusting the focus ring until it was just right.

This process was deeply rewarding.

- You learned the fundamentals: There were no automatic modes to save you. You had to understand the exposure triangle—the relationship between aperture, shutter speed, and ISO—to get a usable image.

- It taught patience: You couldn’t just snap away. You had to wait for the right light, the right moment, and the right composition.

- The result was tangible: Holding a developed negative or a print in your hands is a feeling that a digital file on a screen can’t replicate. The grain, the subtle color shifts—these weren’t flaws; they were the character of the film.

My early digital DSLR cameras were a bridge. They kept the manual controls I loved but added the convenience of an LCD screen and an SD card. Still, the core principle was the same: the lens and sensor captured the light, and I did the rest. The software was mostly a passive participant.

The Dawn of Computational Photography

Then came the smartphone revolution, and with it, computational photography. This isn’t just a better sensor or a sharper lens. It’s a fundamentally different approach where the software is just as important, if not more so, than the hardware.

So, what is it? Simply put, computational photography uses algorithms to assemble a final image from multiple data points. When you press the shutter button on a modern phone, it’s not just taking one picture. It’s often capturing a dozen or more images at different exposures and settings in a fraction of a second. The AI then gets to work, stitching the best parts of each frame together to create a single, optimized photo.

Here’s a simple comparison of the three eras I’ve worked through.

| Feature | Film Photography | Early Digital (DSLR) | Computational Photography |

| Process | Fully manual; mechanical and chemical process. | Manual controls with digital sensor; mostly single-shot capture. | Automated multi-frame capture; software-driven processing. |

| Immediacy | Delayed gratification; requires film development. | Instant preview on an LCD screen. | Instant preview of a fully processed, AI-enhanced image. |

| Low-Light | Requires fast film (grainy), a tripod, and long exposure skills. | Requires a tripod and manual long exposure settings. | Handheld “Night Mode” stacks multiple short exposures. |

| Flexibility | Limited by the film roll you chose (e.g., ISO, color). | High; can change settings on the fly and shoot in RAW. | Extremely high; AI adapts to the scene in real-time. |

| Human Control | Total control over capture, but limited in post-processing. | Total control over capture and extensive post-processing (RAW). | Control over composition, but AI handles much of the technical capture. |

My Initial Skepticism: Resisting the “Magic”

As a photographer who prided himself on understanding the technical side, I was deeply skeptical of these new AI features. They felt like shortcuts that cheapened the craft. A few things, in particular, really bothered me at first.

Portrait Mode and Fake Bokeh

In traditional photography, “bokeh” is the beautiful, blurry background you get when shooting with a wide aperture (a low f-stop number). It’s a direct result of physics—the way the lens renders out-of-focus light. It was a skill to achieve it properly. Portrait Mode on phones simulates this effect using AI. The software identifies the person in the foreground, creates a depth map, and artificially blurs everything else.

My initial reaction was that it looked fake. The edges around a person’s hair were often messy, and the blur didn’t have the creamy, natural quality of a real lens. It felt like a gimmick designed to imitate a professional look without any of the underlying skill.

Night Mode Felt Like Cheating

Capturing a beautiful shot in low light with film was a real challenge. It meant carrying a tripod, carefully calculating a long exposure, and hoping you didn’t get any camera shake. When Night Mode appeared, allowing for crisp, bright handheld shots in near darkness, it felt like a cheat code. The AI was automating a difficult technique that I had spent years trying to master. My purist side saw this as a loss of skill and control.

Overly Aggressive HDR

High Dynamic Range (HDR) is a technique where the camera combines photos taken at different exposures to capture detail in both the brightest highlights and the darkest shadows. My first experiences with smartphone HDR were not great. The results often looked unnatural and flat, with strange halos around objects and none of the beautiful, subtle contrast that makes a photo feel real. It felt like the AI was making artistic decisions for me, and I didn’t like its taste.

The Turning Point: When AI Won Me Over

For a while, I used my phone for quick snaps but always reached for my “real” camera for serious photography. But slowly, I started noticing situations where my phone wasn’t just more convenient—it was getting better results. The technology was improving at an incredible rate, and my skepticism started to fade.

Capturing the “Impossible” Moment

The real turning point was on a family trip. I was trying to get a photo of my niece running through a dimly lit market at dusk. With my DSLR, I would have needed to crank the ISO way up (making the photo grainy) and use a very fast shutter speed. I probably would have ended up with a blurry, noisy mess. On a whim, I pulled out my phone. I just pointed and shot.

The result was stunning. The image was sharp, the colors were vibrant, and my niece was frozen in motion perfectly. The AI had instantly captured a burst of shots, selected the sharpest frames, and used information from all of them to reduce noise. It was a moment I would have missed with my traditional gear. For a deeper dive into the science behind this, Google’s AI blog has some fascinating articles on the technology behind their Pixel cameras. It shows just how much is happening behind the scenes.

The Subtle Genius of Smart Processing

As I paid closer attention, I realized the AI was doing more than just making things brighter or blurrier. It was making intelligent, localized adjustments. The software can now identify different parts of an image—a practice known as semantic segmentation. It recognizes a face and applies subtle skin smoothing while simultaneously sharpening the eyes. It sees the sky and enhances the blue tones without oversaturating the green trees below.

This is something I would spend a lot of time doing manually in editing software like Lightroom. Now, the baseline image I was starting with was already 90% of the way there. The AI was acting like a skilled photo editor, making thousands of tiny decisions in the blink of an eye.

| Pro | Con |

| Incredible Consistency: Greatly reduces the number of technically flawed shots (blurry, under/overexposed). | Risk of “Sameness”: Photos can sometimes have a generic, over-processed look if you don’t learn to control the settings. |

| Access to Difficult Shots: Makes low-light, action, and high-contrast scenes accessible to everyone. | Loss of Technical Skill: It’s easy to forget the fundamentals of exposure when the camera does it all for you. |

| Frees Up Mental Space: Allows the photographer to focus more on composition and storytelling. | Reliance on a “Black Box”: You don’t always know what the AI is doing, which can be frustrating for those who want full control. |

| Excellent Starting Point: The processed JPEGs are often so good they require minimal editing. | Less Malleable Files: While many phones now offer RAW, the “magic” is in the processed file, which has less editing flexibility. |

A New Mindset: Unlearning and Relearning

Adapting to computational photography required me to unlearn some deeply ingrained habits and develop a new way of thinking about capturing an image.

- Unlearning “Expose for the Highlights”: With film and early digital, the golden rule was to avoid “blowing out” your highlights (like a bright sky) because once that information was gone, you could never get it back. With modern HDR, this is far less of a concern. I now trust the camera to handle extreme dynamic range, allowing me to focus more on the subject.

- Relearning to Trust the Preview: With film, you shoot and hope for the best. With computational photography, the live preview on your screen is an incredibly accurate representation of the final, processed image. This means I can adjust my composition in real time based on how the AI is interpreting the scene.

- Embracing Creative Control: Instead of seeing the AI as an adversary, I now see it as a collaborator. My job has shifted from being a pure technician to being a director. I choose the frame, the subject, and the story I want to tell, and I let the technology handle the complex task of capturing the light. If I don’t like the AI’s “perfect” result, I can use pro modes or editing apps to bring back some of the grit and imperfection I loved from my film days.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is computational photography making photographers obsolete?

Not at all. It’s changing the role of the photographer. The technical barrier to getting a well-exposed photo is lower, but the need for a good eye, strong composition, and storytelling ability is more important than ever. The tool changes, but the art remains.

Can you still be creative with an AI-powered camera?

Absolutely. Creativity is about vision, not just technical settings. AI handles the technical execution, freeing you up to experiment with angles, perspectives, and subject matter you might have avoided before because they were too technically difficult to capture.

Do professional photographers use their phones?

Yes, many do. While a high-end camera is still the tool of choice for commercial shoots, many professional photographers use their phones for personal work, street photography, and situations where a large camera would be intrusive. The best camera is the one you have with you.

Which is more important: a good lens or good software?

Today, they are equally important. Incredible hardware with poor software will produce mediocre results, and brilliant software can’t fully overcome the physical limitations of a tiny lens and sensor. The magic of modern photography happens when they work together seamlessly.

Conclusion: A New Partner in Creativity

My journey from the darkroom to the algorithm has been one of initial resistance, slow acceptance, and finally, genuine appreciation. I still own and love my film camera. I use it when I want to slow down and reconnect with the deliberate, manual process of creating a photograph from scratch.

But I no longer see my phone’s camera as a toy or a cheat. It’s an astonishingly powerful tool that has opened up new creative possibilities. Computational photography didn’t kill the craft; it just changed the skillset. The heavy lifting has shifted from mastering f-stops and shutter speeds to honing your creative vision. The AI takes care of the complex math of light capture, allowing me—the photographer—to focus on the one thing it can’t replicate: telling a compelling story.